Inventing Miracle:

The Rice to Power

Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson & Marcos Ferdinand visit IRRI facilities. Image credit: International Rice Research Institute Archive

Inventing Miracle: The Rice to Power

Chu Hao Pei

Overlooked in the Cold War, the proliferation of ‘Miracle Rice’, IR-8, provided a new kind of space from which to understand the Cold War. As Gen. Robert Komer, the chief of Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support (CORDS), the pacification command, advertised a new policy in Vietnam with the slogan “rice is as important as bullets.”1, the ‘Miracle Rice’ illustrated how rice technology could be employed for pacification and to consolidate US’s client regimes.

Apart from defining their national political ideologies through revolutionary struggles or transitional ‘peaceful’ handovers from their colonial masters, most Southeast Asian nations were also facing severe food shortages with a booming post-war population. While wars and political upheavals like the Vietnam War, the growing communist presence in Indochina, the communist insurgency in Malaya and the military coup in Indonesia, dominated the Cold War arena in Southeast Asia, another type of ‘war’ took shape in the rice fields under the name of ‘food sufficiency’.

Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson & Marcos Ferdinand visit IRRI facilities. Image credit: International Rice Research Institute Archive

Food was crucial to any regime in power and keeping starvation at bay in any one nation was equally as important as counter-balancing the tussle between the political left and right. In light of the void of a self-sufficient staple food crop, the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) was formed with the support of Ford and Rockefeller Foundation in the Philippines, with the ambition to develop a new variety of rice to eradicate food shortage. In 1966, the newly invented ‘Miracle Rice’ was inaugurated by then US President Lyndon B. Johnson in Los Banõs, the headquarters of IRRI. Together with the Green Revolution, the ‘Miracle Rice’ became a convenient vehicle for resolving the food insufficiency as a strategy to integrate nations into the capitalist bloc. Nations that have embraced the ‘Miracle Rice’, coincidentally, are US-aligned dictatorial regimes - The Philippines, Indonesia and Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam). The spread of the ‘Miracle Rice’ grew in tandem with the aggressive agricultural policies adopted by Indonesia, Philippines (Masagana 99) and Republic of Vietnam (Vo Dat experiment & Accelerated Miracle Rice Production Program2) in pursuit of rice sufficiency.

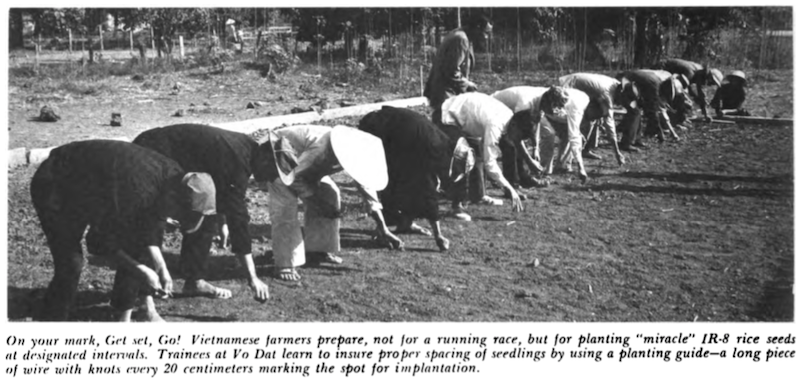

War on Hunger: A Report from the Agency for International Development, Vol. II, No. 10, Oct 1968, p. 4

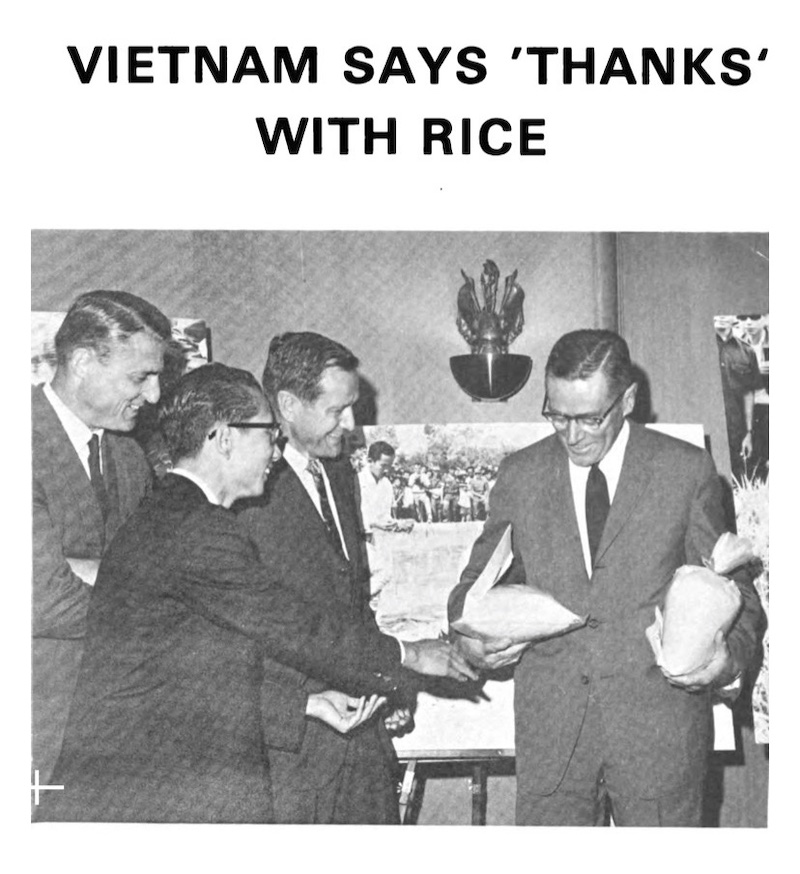

USAID Administrator William S. Gaud (right) holds two bags of IR-8 “miracle” rice harvested at Vo Dat, in South Vietnam, presented to him by South Vietnamese Ambassador Bui Diem (foreground) at an October 2 ceremony in Washington. Image credit: War on Hunger: A Report from the Agency for International Development, Vol. II, No. 12, Dec 1968, p. 16

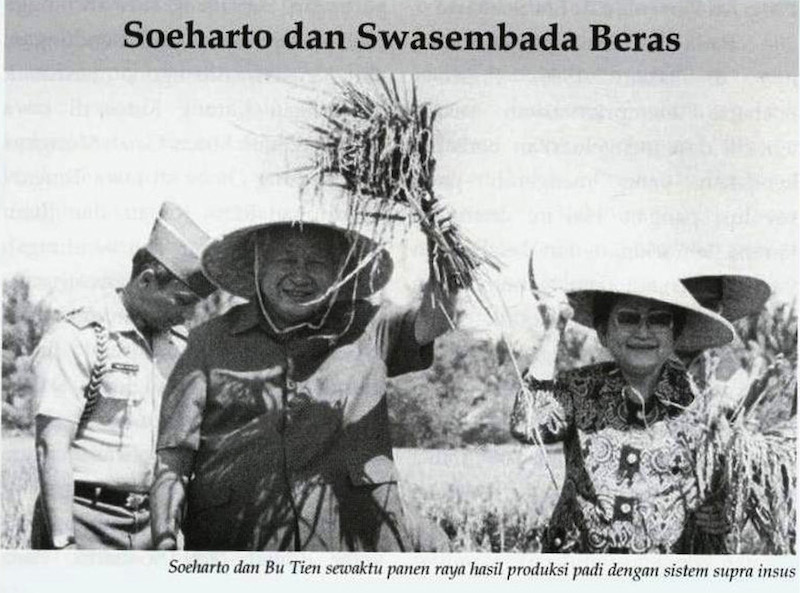

Nowhere has the ‘Miracle Rice’ been so effective in facilitating the leaders to power more than the Philippines, allowing Marcos Ferdinand to sweep to victories in 1965, under the slogan “Progress Is a Grain of Rice”3, and his reelection in 1969. However, the illusion of rice sufficiency with IR-8 for both the Philippines and Indonesia were short-lived and soon fell apart, contributing to the former’s fall from grace in the 70s and the latter diverting attention to subsequent controversial and failed rice agriculture policies (Supra Insus & Mega Rice Project4). Towards the conclusion of the Vietnam War, the ‘Miracle Rice’ was used as a leverage by the US on the negotiation table with Hanoi and became part of a reorganised pacification effort designed to foster an image of South Vietnam as a self-supporting state capable of surviving a peace settlement5 where American planes leafletted North Vietnam with photographs of dwarf rice fields captioned “IR-8, South Vietnam’s Miracle Rice. All Vietnamese can enjoy this rice when peace comes.”6 The ‘Miracle Rice’ has manifested into different forms of political trajectories in soliciting nations into the capitalist bloc. Undeniably, ‘Miracle Rice’ has shifted the course of the Cold War in a non-belligerent approach through the use of psychological warfare.

Soeharto dan Swasembada Beras (Suharto and Rice sufficiency). Image credit: Diplomasi Journal Vol. 3 No. 3, Sep 2011, p. 219

The paradoxical ‘Miracle Rice’ was designed to symbolize and enforce modern rationality, but it fulfilled a yearning for magic at a time where food shortage was severe. In the gap between the ‘Miracle Rice’ true capabilities and its miraculous claims flowed the ambitions of the United States. The ‘Miracle Rice’ became an instrument of U.S. policy in Asia’s Cold War.

Inventing Miracle: The Rice to Power. Video courtesy of Chu Hao Pei

References

-

Komer, R. W. (1966, July 1). Memorandum From the Presidentʼs Special Assistant (Komer) to President Johnson. U.S. Department of State. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v04/d171.

-

Tran Quang Minh. (2015). ‘Ch. 4: A Decade of Public Service: Nation-building during the Interregnum and Second Republic (1964–75)’ in Voices from the Second Republic of South Vietnam (1967–1975), 63.

-

Cullather, N. (2004). Miracles of Modernization: The Green Revolution and the Apotheosis of Technology. The SHAFR GuideOnline, 28(2), 243. https://doi.org/10.1163/2468-1733_shafr_sim210040064

-

Goldstein, Jenny. “Carbon Bomb: Indonesia’s Failed Mega Rice Project.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2016), no. 6. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7474.

-

Bunker to AID, “New Pacification Concepts,” 26 September 1968, Declassified Documents Reference System (Bethesda, MD[microfiche], 1995), fiche, 1995-88: 1003.

-

Robert W. Chandler, War of Ideas: The U.S. Propaganda Campaign in Vietnam (Boulder, CO, 1981), 108-109.

Further Reading

Bruce Nussbaum (2017) ‘Miracle Rice’ in Design and Violence #3 (2017) MOMA & Science Gallery Dublin. A Green Revolution Turns Red, Jan 8 1970, The New York Times.

Keywords: chemical fertilisers, heirloom seeds, mechanisation, political tool, shortage, sufficiency, yield

Published 31 August 2021