Notations on rice, absence and grief

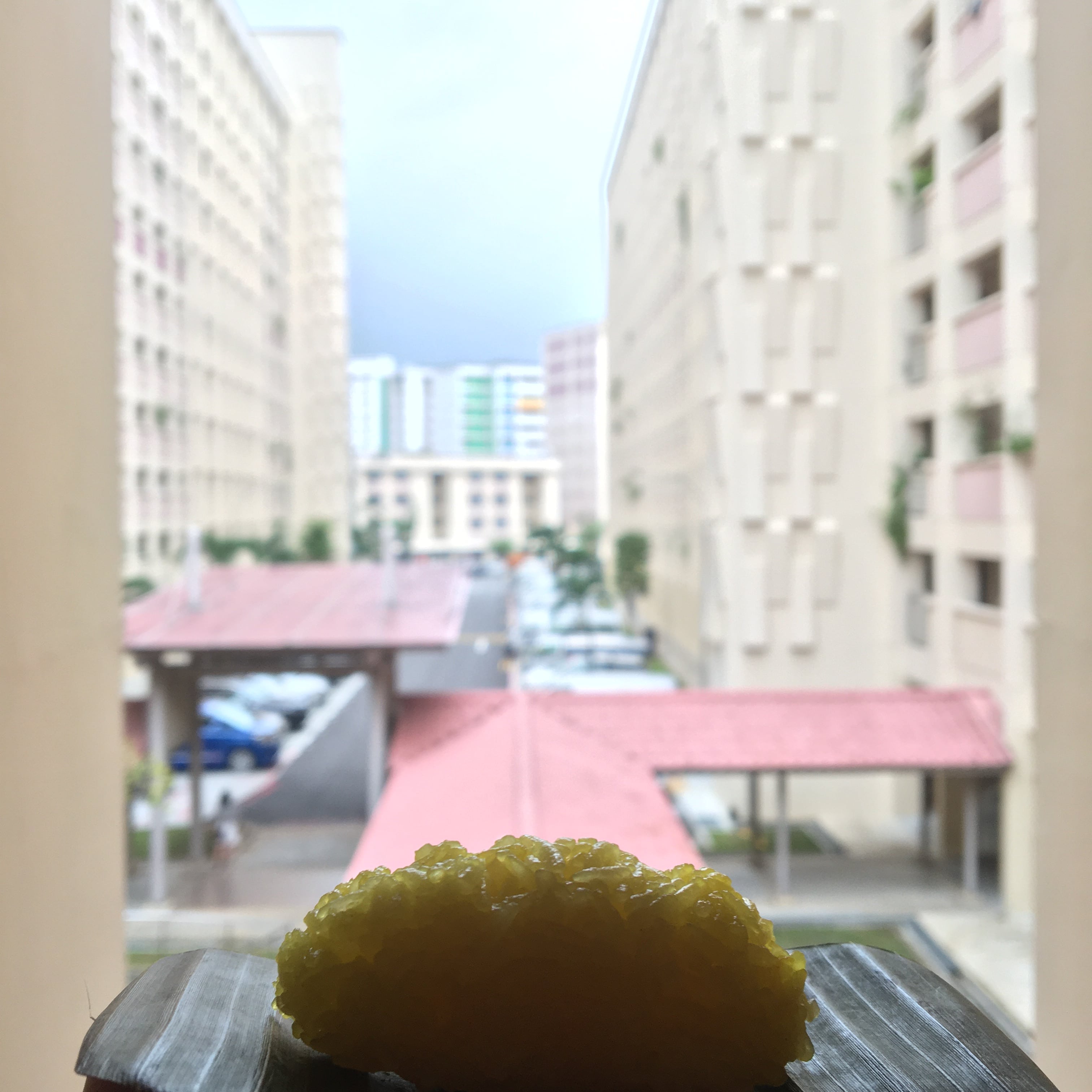

making pulut kuning using glutinous rice and turmeric. Image credit: Kamiliah Bahdar

Notations on rice, absence and grief

Kamiliah Bahdar

Abstract:

Expanding from two recent projects — Pulut Something: Form and meaning, a letter exchange between Syaheedah Iskandar and myself on glutinous rice and the familial relations and stories it evokes; and Pertiwi, an on-going conversation and collaboration between Savitri Sastrawan and myself on the Goddess Pertiwi as a guiding figure on such notions as care, well-being and resilience—this narrative piece weaves fragments from research, conversations with Hao Pei on and personal encounters with rice: its rich significance, its closeness and distance, and as medium for cultural and spiritual connection and loss.

A TREE REMOVED

There was a thin scraggly tree that used to stand outside my bedroom window, on a small patch of grass surrounded by concrete. It was more twigs than leaves, yet it seemed a favourite among birds. Lone crows came breaking off bundles of twigs for their nests. Other times, it was the stage for male orioles to perform their mating calls. Once, a pair of Sunda pygmy woodpeckers were hovering about and drumming into the trunk and thick branches. There was a quiet contentment in observing, the kind that took me out of myself.

When they came to cut it down, it started with pruning the branches, then moving from top to bottom in sections till nothing was left but a small circular clearing in the grass patch. Mornings stopped resonating with the dawn chorus of birds like it used to.

The view outside my window is now two parallel concrete facades—immovable and implacable. Against this brusque backdrop, the erasure seemed inconsequential. And though the severance of an amorphous intangible connection felt all too familiar, I wonder how long this feeling of absence will stay, and how I might grieve this callous act of removal.

FRACTURES OF MEMORIES

For a letter exchange between Syaheedah Iskandar and myself (pulausomething.space > Fragments > Pulut Something: Form and meaning), we each learned from our mothers how to make a traditional glutinous rice dish, jotting down the recipes as we do–her the bubur pulut hitam, me the pulut kuning. Rereading my letter to her (and the annotations by Nurul Huda Rashid, ‘Make it glitter and gleam’), I see again the theme of ruptured connections: an estrangement from place, culture, and history. Or rather, an estrangement from the memory of a place, culture, and history: Of a land with gleaming and glittering golden rice fields; of rice, fruit of the earth, finding expression as a symbol for the divine gift of life in the pulut kuning dish; and the history of myths, folklores, beliefs, and rituals that connects the two.

It is perhaps true for myself to say that the place has always been imagined, and the history only remembered in fragments. The pulut kuning, though, still grace celebrations–often weddings, sometimes birthdays–signifying blessing, prosperity and good fortune. However, when I dwell on it too long, there seems to be a two-fold alienation: of me from the fecund environment it harkens to, and the pulut kuning from the urban environment it has been transplanted to. In an ironic turn, the pulut kuning for me has come to be about absence and grief. (Are there foods for sad occasions?)

A RE-ENACTMENT

I have been wanting for a while to recreate the pulut kuning served to me on my homecoming by two elderly sisters in Binjai, North Sumatra: Partly to manifest a memory that was starting to fade; partly to return (to a somewhere, as though I am a person of diaspora, although that somewhere oftentimes is unfamiliar and strange, and that somewhere is more imagined than real) however briefly, and in that brief return to grasp desperately at fragments to remember and to reconnect.

Image credit: Kamiliah Bahdar

I remembered it to be individually hand-shaped oblong rolls resting on a banana leaf. From a plate of freshly steamed pulut kuning left to cool down a bit, I scooped with my hand what I deemed an appropriate amount. Clumps of rice stuck to my skin here and there, as though demonstrating a certain wilfulness to hold dear (and I am reminded of the words terlekat, to stick, and terpikat, smittened, used by both Syaheedah and Nurul). The act of shaping it turned out to be an intimate one. I used both hands to pack the sticky rice, then rolled it gently along the palm of one hand, and pinched the ends. While it was in my hand it looked more like sushi, but after placing it on the banana leaf, it looked like a mound of gold on a green field.

I carried this small mound of gold outside, wanting to juxtapose the representation of the rice field in miniature against the large impersonal geometric buildings, thinking it could function as a kind of memento while grieving. But it did not call me to grieve. It asserted its presence beyond merely the symbolic. In these abstract meanderings, I sometimes forget that there is a material substance to rice–firm and dense, nourishing and hearty–that gives form to its spiritual substance. And that merely in preparing and consuming, we are reproducing a cultural memory and enacting a connection to all it has touched.

Maybe it was a little too hasty of me to say that the pulut kuning is a reminder of absence and grief. I suppose it is inevitable that it would come to hold multiple contradictory meanings as our lives and surroundings change. Now near where the tree used to be there is a young tree growing steadily and healthily to slowly fill a void.

ALTERED LANDSCAPE

Although, I know, even the view of flats from my window will be gone, replaced by another that is taller and denser, obscuring the sun and moon.

I toyed with making the pulut kuning into a rectangular edifice, in a process that was more removed, using a spoon to paddle it into a four-sided shape and a knife for straight sharp edges. Then I cling-wrapped it and used aluminium foil over the banana leaf in an attempt to repackage the pulut kuning to mimic a radically altered landscape, like the glass and steel of high-rise buildings, and a different cultural and temporal environment, where foodstuffs are pedestrian commodities serving convenience (the trap that the ketupat has fallen into: where before it was made with palm leaves, it now comes in plastic packets). It made for a strange object, at once familiar and unfamiliar.

Maybe it will resist change yet.

Image credit: Kamiliah Bahdar

Keywords: amnesia, moyang, traditions, spiritual, sacred foods

Published 18 October 2021

Singapore